Who ever thought in the first place that the solution to too much email was a flood of group chat?

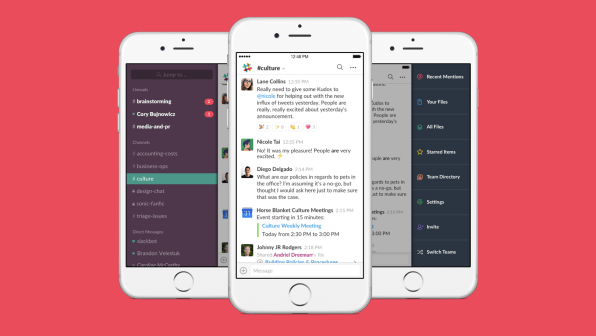

Obviously, many of us did because in recent years plenty of tech-savvy professionals have rhapsodized about Slack, the group messaging app and highly valued startup, as the holy grail of office communication and collaboration. Valued at $2.8 billion, it has 2.3 million active users, 675,000 of them with paid accounts, which is pretty impressive for a company that just launched in February 2014.

Slack still has plenty of admirers, but in recent months a surge of critics have started to get more vocal. There is even a (modestly trafficked) Twitter hashtag for griping called #Slacklash. There has been scattered grumbling over the years, but what really kicked off the conversation was user experience designer Samuel Hulick’s laugh-out-loud essay on Medium in February, titled “Slack, I’m Breaking Up with You.”

“Email may have had its flaws with its ‘FWD: FWD: CC: FWD You have to read this!!1!’ jokes sent from distant family members,” writes Hulick, “but my god in heaven do those sound like the halcyon days of tranquility compared to the Diet-Coke-and-Mentos-like explosion of cat gifs, bot feeds, and emoji mashups you’ve brought into my life.” Even detractors like Hulick are torn, though. He professes as much love for Slack as frustration. In the end, Hulick comes to the painful conclusion that the relationship just isn’t right for him.

The ebb and flow of opinion about Slack is fairly typical, say experts. “Technology goes through this very predictable pattern of adoption,” says Jerry Kane, a professor of information systems at Boston College’s Carroll School of Management. “A tool comes along. It’s the best thing since sliced bread, and everybody joins in. And then they realize, well, it’s not magic. There are pros and cons. And then it goes into the trough of disillusionment.”

IT’S IN THE WAY THAT YOU USE IT

Another critical essay on Medium titled “Is Group Chat Making You Sweat?” by Jason Fried, takes a more nuanced approach. That’s not surprising, since he is the founder and CEO of Basecamp—collaboration software that relies heavily on chat. Fried’s argument is that group chat can be good or bad, depending on how you use it.

Built for instant communication, chat is great for just that—dealing with emergencies such as a server that goes down. It’s not good for ongoing conversations where important decisions may be made, without input from some people who are too busy working to constantly watch Slack discussions.

“This is the fatal flaw. You can’t guarantee people are going to see something on Slack,” says Jason Kolb, who was CTO at fast-growing company Uptake, which analyzes sensor data from industrial machines. Uptake tried to use Slack, says Kolb, but as the company grew in a year and a half from fewer than 10 people to about 400, the conversations got too chatty and superfluous—with jokes, animated GIFs, and such. Employees stuck with email for any important conversations. Uptake eventually abandoned Slack as a company-wide communications tool, but its small teams of programmers kept the app. “People working on the same things in the same teams tend to use it,” he says.

That makes sense, says Kane, who teaches a course on social media and digital business. As individuals and as employees, we are incorporating several forms of communication side by side, and using the one that makes the most sense for each situation. “If you expect to use [Slack] uncritically for all tasks, it’s not going to do that,” says Kane. “It’s going to be good for certain types of interactions and communications.”

One of the best uses of a chat environment, he says, is for someone to put out a question that a number of people could answer: Everyone doesn’t have to read every message for this to work. Since Slack archives communications and has good search features, that information is preserved for others to find. Kane gets the same result by using Twitter with his students.

Despite Kane’s feeling that people don’t need to be on Slack all the time, they are there quite a bit. At the recent South by Southwest Interactive conference, quasi-celebrity Slack CEO (and Flickr cofounder) Stewart Butterfield said that Slack users, on average, spend two hours and 20 minutes a day actively using the app, and possibly more time watching it.

One of the reasons people feel frustrated with Slack may be its reputation as an “email killer,” based on proclamatory headlines by tech and business publications: “Slack Is Killing Email” (The Verge), “How E-Mail Killer Slack Will Change the Future of Work” (Time), “Slack, the Office Messaging App That May Finally Sink Email” (New York Times), “Flickr Cofounders Launch Slack, an Email Killer” (yes, Fast Company). This is more than Butterfield has promised. “Email is the lowest common denominator,” he told The Verge in that same article. “It’s the way you get communications from one person to another. There isn’t really an alternative.” (Slack declined to make someone available for an interview, but it did send some input by email.)

STOP THE MADNESS

Not all of Slack’s users—many of them new to chat apps—have figured out how to pace themselves. Not only are they posting all kinds of superfluity (the phrase “water cooler” comes up in conversations about the app), they are also raising expectations for everyone in the office to be readily available. Part of that could be how trendy Slack has become, fueled by the increasing movement in the direction of an always-on life and aided by technologies such as smartphones. “I think timing makes a big difference. If we had launched three years before we did, it wouldn’t have taken off,” said Butterfield at SXSW.

There may be a psychological underpinning to this, says Linda Stone, who writes about attention and distraction. “In some contexts, a group chat is a good match for the content and intentions of the group. In some cases, it can be a stringy distraction,” she writes in an email to Fast Company. In his Medium essay, Hulick references Stone’s coinage, the term continuous partial attention. “We want to effectively scan for opportunity and optimize for the best opportunities, activities, and contacts, in any given moment,” Stone writes in an essay about the concept. “To be busy, to be connected, is to be alive, to be recognized, and to matter.” That’s a lot to expect out of business software.

Even if Slack is used in a focused way, it can get out of hand. “I’m finding that ‘always on’ tendency to be a self-perpetuating feedback loop: The more everyone’s hanging out, the more conversations take place. The more conversations, the more everyone’s expected to participate,” writes Hulick. There are limits to how much people can multitask, or apply continuous partial attention.

“We have to be very careful in an attention economy, to be efficient in the information flows that we create,” says Sinan Aral, a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management who has also worked in the startup world of apps, social media, and marketing tech. “Beyond a certain number of optimal projects . . . you start to experience diminishing and negative returns to multitasking behavior.”

There hasn’t yet been any published research on the impact of Slack on productivity. But there is a recent study on Jive, a social network for offices, by Paul Leonardi, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Leonardi did an experiment with employees at Discover Financial Services, which has 15,000 people on staff. He divided about 70 of them into two groups. One used Jive, which is a bit like Facebook for office workers, for six months; the other group didn’t use Jive at all. The group on Jive wound up with a much better understanding of the expertise of each of their coworkers, as well as a better understanding of who knew whom—positive results that wouldn’t shock anyone who’s used Facebook.b

But studies on email show some potential downsides. Even though Slack is supposed to be an email killer, both platforms can pose similar dangers of overtaxing people’s attention. One study, by Kostadin Kushlev and Elizabeth Dunn at the University of British Columbia, broke into the popular press with a January 2015 article they published in the New York Times titled “Stop Checking Email So Often.”

Half of the 124 people in their study were told to check email as much as possible, with their app open and email alerts on—which sounds a bit like being on Slack. The other half was allowed to check email only three times per day. The second group reported being way calmer—as they would be if doing relaxation exercises throughout the day, compared to the people who were always online. They also got more done. “An unfortunate limitation of the human mind is that it cannot perform two demanding tasks simultaneously, so flipping back and forth between two different tasks saps cognitive resources,” they wrote. “In addition to providing an unending source of new tasks for our to-do lists, email could also be making us less efficient at accomplishing those tasks.” Imagine that with not just two tasks but a half-dozen Slack channels.

THE SOFTWARE MADE ME DO IT

If chat goes off the rails, whose fault it is? Do apps like Slack create a new environment that people have to adapt to? “Every software product comes with its own bias towards supporting some human tendencies over others, and I don’t think it’s arguable that you skew pretty hard towards ‘always on’ over ‘dip in every so often,’” writes Hulick. Or as Aral puts it, “Certain features, the default settings and so on, can create path dependencies and usher users into a certain mode of using the technology.”

There are various features that Slack users are clamoring for—ones common to that dinosaur tech called email. One of the most popular is threaded conversations, to condense the torrent of comments into packages. The company says that threading is coming. Slack also lacks something like an out-of-office autoresponder. It will show, by diming the dot next to someone’s name, if they are currently inactive (away from their computer for a half hour or out of the mobile app for a half minute). Slack also provides a do-not-disturb setting. But there’s no way to indicate if the person will be away for five minutes or five days.

In addition to basic features, could Slack proactively help tamp down the noise by, for example, not allowing animated GIFs by default? Could it be configured to cap how many messages someone could send per minute, hour, or day? Could it allow people to set up a mute or filter for colleagues who always post garbage? What about a Reddit-style upvoting mechanism to make the best posts or answers to questions appear more prominently? One of the commenters on Hulick’s essay suggested a system of reputation points like on Stack Overflow, a community discussion site for programmers—highlighting team members who are most helpful and discouraging people from posting garbage that lowers their reputation value.

Slack’s new office in New York City houses its Search, Learning, and Intelligence group. “Our goal is to make people feel less overwhelmed by Slack’s information avalanche,” wrote Noah Weiss, who left Foursquare to head the new group. In a post on Medium, Weiss named search and information retrieval, recommendation systems, natural language processing, and machine learning artificial intelligence as areas on which his team will work. CEO Butterfield said at a February Wall Street Journal conference that artificial intelligence might someday help reduce the flow of messages by, for example, auto-summarizing conversations. He also said that he is skeptical that such AI will be effective anytime soon.

One thing that’s clear: The company itself believes it can do better, as Butterfield is known to say rather bluntly. “I feel that what we have right now is just a giant piece of shit. Like, it’s just terrible and we should be humiliated that we offer this to the public,” he told MIT Technology Review in a November 2014 interview. “This is still as true now as it was 16 months ago,” he just tweeted in February. “. . . But: we’re working on it!”